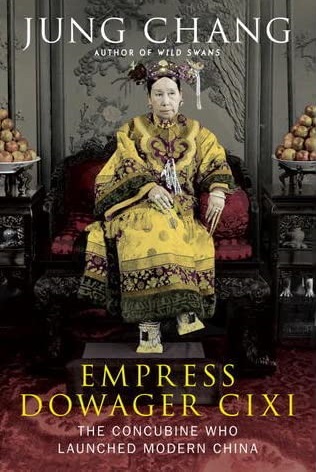

Jung Chang

Ostensibly a biography researched and written by Jung Chang, it illuminates more than the life of “the Concubine Who Launched Modern China” but also how perceptions of her beyond China were influenced by orientalism. Edward Said (1978) conceived of the practice of orientalism as a way in which the Asian region was defined and located as Europe’s “other”. It both homogenised yet exoticised Asians including the China nation-state. It also implied European forms of knowledge represented intellectual and cultural mastery to which othered peoples could only hope to aspire. This book rejects the Western lens and provides an alternative story of a woman who is credited with leading China into the modern age.

Jung Chang cleverly provides a portrait of a woman who was the de facto supreme ruler of China in the late Qing Dynasty for almost half a century. From concubine, to Empress Dowager and Regent, Cixi challenged what were accepted norms and concepts of traditional rules. She shared rule with Empress Dowager Ci’an for a period representing a strong partnership and collaborative approach that is not often acknowledged as possible in Western ideas of womanhood. Author Jung Chung explores the previous portrayals and perceptions of Cixi and her actions, highlighting the Eurocentric Western gaze. Ultimately, Jung goes on to present a plethora of evidence as to how past views of Cixi were perhaps overly simplistic and erroneously vilifying. Jung deftly brings to light many complexities of situations and political intrigues Cixi faced.

While Cixi is celebrated as leading China to modernisation, Jung explores the assumptions that the nation had previously languished in its cultural traditions. However, the position of China in the global community is often shaped by a commonly held misconception (in the West) that neglects consideration of the nation’s modern history, repeatedly ravaged and undermined by European invasions and imperialist impositions. Jung Chang creates a thoughtfully deep look at what this iconic leader achieved in a rapidly evolving political environment which had wrought significant cost to China. It might be deemed a homage to Cixi given the text challenges Western tellings of her supposedly tyrannical obsession with power and aggressive responses to political plots.

I felt that Jung artfully provided a balance in acknowledging Cixi’s shortcomings and triumphs, detailing her failures and successes in striving toward her visionary aspirations for China. The extensively researched book also provides insights into Cixi’s personal life by examining her own writing, with additional context from the perspectives of other key players situated in her court.

Cixi is often demonised and villified, as if she had been a woman drunk on power, anxiously protective of a delicate ego. Jung Chang deftly interweaves considerable evidence to suggest that such portrayals are more a function of how modern historiology has often struggled with detailing the lives and influences of powerful and empowered women. These omissions have also failed to acknowledge the intricacies of women navigating intersecting power dynamics while simultaneously managing social constructions of womanhood.

“Empress Dowager Cixi” is a fascinating read that creates a deep and thoughtfully complex portrayal of a woman who oversaw one of China’s most significant periods of change, leaving a weighty legacy for “the Last Emperor” Pu Yi.